Hurricanes

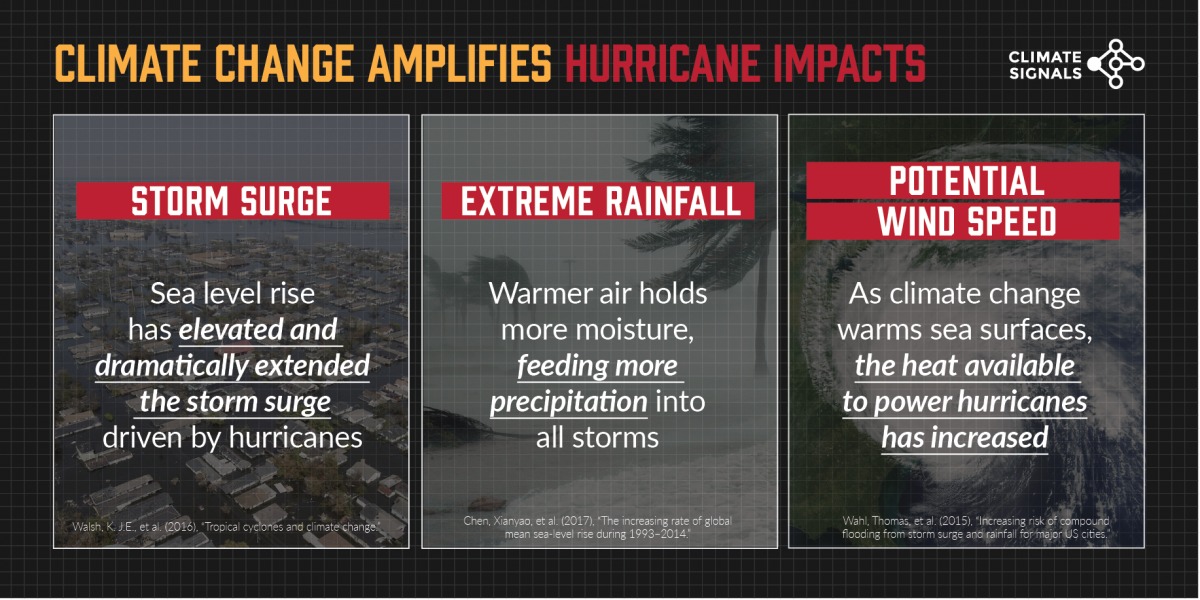

Increases in air and ocean temperatures due to climate change are having wide-ranging effects on hurricane precipitation, intensity, and coastal flooding. Warmer temperatures increase the rate of water evaporation from land and sea surfaces, which feeds moisture and energy into storms. Warmer air can hold more moisture, which increases the amount of water available for storms to dump out as rain. Additionally, warming oceans and melting land ice have caused sea level rise, which boosts storm surges, the name for the temporary increase in sea level due to storm conditions.

How has climate change already worsened hurricanes?

Climate change is leading to more intense hurricanes, as measured by wind or central pressure.

In almost every region of the world where hurricanes form, their maximum sustained winds are getting stronger due to human-caused climate change.[12]

Climate change is contributing to sea surface temperature increases in the Atlantic and Pacific regions where hurricanes form, increasing the energy available to intensifying storms.[13][14]

Global warming has likely increased the relative number of hurricanes reaching Category 3 intensity or higher since the 1980s.[12][15][16]

What are hurricanes?

At the most basic level, a hurricane is a type of storm, and a storm is any interruption of the prevailing atmospheric pressure and wind fields that causes high winds and precipitation. Storms that form in the tropics are called tropical cyclones. When a tropical storm’s maximum sustained winds reach 74 mph, it is called a hurricane. Hurricane intensity is usually measured by a storm’s wind speed. Category 5 hurricanes are the most intense and have wind speeds of 157 miles per hour or higher.

How does climate change affect hurricane intensity?

Warmer ocean water due to climate change strengthens hurricanes and other storms that feed on heat energy from bodies of waters, effectively increasing how powerful a storm can become.[20] Some of the substantial evidence that climate change is intensifying hurricanes shows a global increase in the proportion of storms reaching Category 3 strength or higher[12] and in the intensity of the strongest storms.[21][22] The biggest and most damaging hurricanes are now three times more frequent than they were 100 years ago.[23]

How does climate change affect Atlantic Ocean hurricane activity?

In the Atlantic, climate change is likely responsible for long‐term trends in cyclone activity.[24]Scientists identified the fingerprint of climate change in the increase in the number of hurricanes occurring in the North Atlantic since the 1980.[25] Unusually warm sea surface temperatures likely played a key role in the active 2017 Atlantic hurricane season.[26] From 2016 to 2019, the Atlantic basin had the most consecutive years on record with at least one Category 5 storm, topping the last record set from 2003 to 2005.[27]

How does climate change affect Pacific Ocean hurricane activity?

Climate change is also behind the observed increase in hurricane activity in the Central Pacific since 1980,[25] and the fingerprint of climate change has been found in the unusually active 2015 eastern Pacific[28] and 2014 central Pacific[29] hurricane seasons. Climate change has also substantially increased the risk of having an extremely intense tropical cyclone season in the Western North Pacific, like the one observed in 2015.[30]

Events spotlight: climate change and recent hurricanes

Tropical Storm Imelda (Texas, 2019)

Imelda brought over 43 inches of rain to Southeast Texas in September 2019, making it the fifth wettest storm on record in the continental US. Climate change made the extreme rainfall and flooding caused by Tropical Storm Imelda more likely and intense.[11]

Hurricane Florence (North Carolina, 2018)

Florence brought up to 36 inches of rain to North Carolina in September 2018, and is the ninth wettest storm on record in the continental US. Human-caused climate change has increased rainfall during recent hurricanes in North Carolina,[2] including Hurricane Florence.[1][31] Because of sea level rise, Hurricane Florence flooded an additional 11,000 homes that would have otherwise stayed dry.[17]

Hurricane Maria (Puerto Rico, 2017)

Maria devastated Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands and is one of the costliest storms in US history at $93.6 billion. A storm of Maria's rain magnitude is nearly five times more likely to occur today, with warmer air and ocean water, than it would have been in the 1950s, when global warming's effects were minimal.[3]

Hurricane Harvey (Texas, 2017)

Harvey is the wettest tropical cyclone on record in the US and the second costliest weather or climate event in US history, second only to Hurricane Katrina. By one estimate, up to two-thirds (or $67 billion) of Hurricane Harvey's $90 billion price tag is attributable to human-caused climate change.[32] Four studies identified the fingerprint of climate change on Harvey’s extreme precipitation,[5][6][7][8] and two studies attributed the record-high sea surface temperatures that sustained and intensified Harvey’s rainfall to climate change.[5][33]

Hurricane Sandy (New York & New Jersey, 2012)

Sandy cost $65 billion, making it the fifth most expensive weather or climate event in US history. Human-caused sea level rise extended the reach of Hurricane Sandy by 27 square miles, affecting 83,000 additional people in New Jersey and New York City and adding over $2 billion in storm damage.[18]Climate change also contributed to the volume of moisture in the atmosphere during Hurricane Sandy.[9]

Hurricane Katrina (Louisiana, 2005)

Katrina was one of the worst natural disasters in US history, causing a record $152.5 billion in damages and more than 1,800 deaths, and displacing 1.2 million people. A wetter atmosphere due to climate change increased Hurricane Katrina's rainfall.[4][10] Hurricane Katrina would have flooded 60 percent less area of New Orleans had the storm occurred in 1900, before land subsidence and climate change increased sea levels by 30 inches.[19]

The social impacts of climate change and worsening hurricanes in the US

Low-income communities, indigenous communities, and other communities of color in the US stand to suffer the most and have the fewest resources to cope as climate change increases hurricane risks.

Hurricane Katrina is an iconic example of how climate change impacts compound racial and economic inequality. When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, the impacts were disproportionately borne by the Black community. The hardest hit areas in the New Orleans and Biloxi-Gulfport coastal regions were 46 percent Black and 21 percent poor compared to undamaged areas which were 26 percent Back and 15 percent poor. In New Orleans, the mortality rate for Black residents aged 18 or older was up to 4 times greater than that of White residents. Also in New Orleans, disparities in cardiovascular disease ratesbetween Black and White older adults were exacerbated during and following landfall. Racial disparities in economic outcomes of Katrina survivors are also evident in unemployment rates, as well as in reports of difficulties accessing healthcare and of general life disruption. Black people reported greater levels of stress than White people in the aftermath of Katrina, and greater levels of anger and depression.

Katrina is not an isolated case. Black and Latino residents and those with lower incomes reported the highest rates of property and income loss after Hurricane Harvey. In New Jersey, Hurricane Sandy disproportionately impacted low-income families, who incurred 53 percent of residential expenses and receiving only 27 percent of resources. In New York City, the poverty rate in areas flooded by Sandy was higher than that in dry tracts, and Black New Yorkers and poor blacks in particular were more likely to live in flooded areas. Similarly, low-income communities and communities of color in North Carolina were disproportionately impacted by Hurricane Florence.

Sign Up to receive Hurricanes Thought Leadership

Form temporarily disabled.