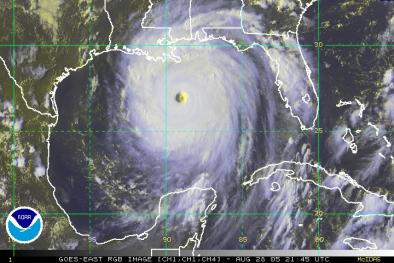

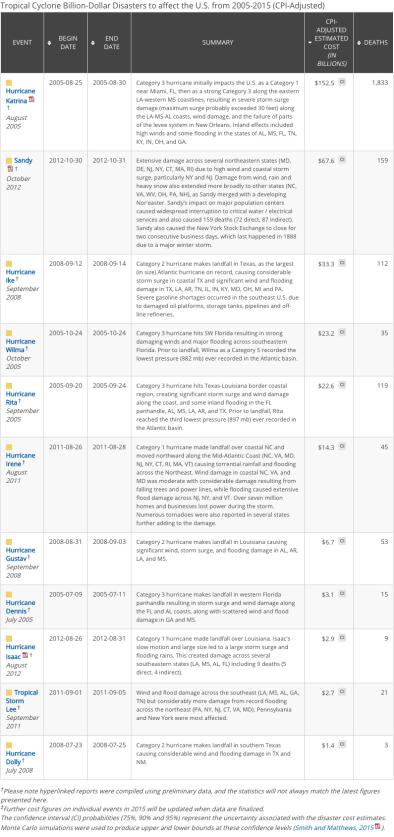

Hurricane Katrina 2005

Hurricane Katrina was one of the worst natural disasters in US history, causing US $170 billion in damages, more than 1,800 deaths and displacing 1.2 million people. Climate change contributed to the severity of Katrina's storm surge, increased Katrina's rainfall, and may have contributed to the storm's intensity. Katrina is an iconic example of how the impacts of climate change are disproportionately felt by low-income communities and communities of color. Systemic and structural inequities that keep incomes low made certain neighborhoods vulnerable to flooding and limited access to medical care.

Climate science at a glance

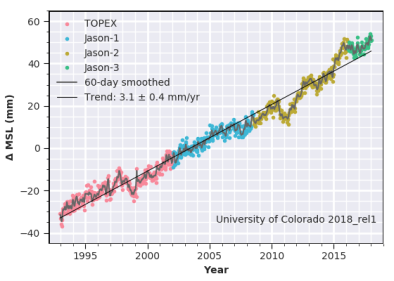

- Flood elevations during Katrina would have been 15 to 60 percent lower around 1900 than the conditions observed in 2005.[1] Between 1900 and 2005, in New Orleans rose 0.75 meters, 0.57 of which was due to land subsidence.[2]

- Climate change worsened Hurricane Katrina's rainfall.[13]

- Scientists estimate a doubling of Katrina magnitude events associated with the warming over the 20th century.[3]

Meet Hurricane Katrina—the costliest hurricane in US history

In the US, hurricanes accounted for seven out of ten of the costliest natural disasters from 1980-2014, and Hurricane Katrina—which devastated the US Gulf coast in August 2005—tops the list.[4] Katrina cost $170 billion in damages, caused more than 1,800 deaths and displaced 1.2 million people.[5][6]

Hurricane Katrina disproportionately impacted low-income and Black communities

When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, the impacts to life and property were disproportionately borne by the Black community. The hardest hit areas in the New Orleans and Biloxi-Gulfport coastal regions were 46 percent Black and 21 percent poor compared to undamaged areas which were 26 percent Back and 15 percent poor. In New Orleans, which was 68 percent Black, an outsized 84 percent of missing people were Black, and the mortality rate for black residents aged 18 or older was up to 4 times greater than that of White residents. Also in New Orleans, disparities in cardiovascular disease rates between Black and White older adults were exacerbated during and following landfall. Racial disparities in economic outcomes of Katrina survivors are also evident in unemployment rates, as well as in reports of difficulties accessing healthcare and of general life disruption. Black people reported greater levels of stress than White people in the aftermath of Katrina, and greater levels of anger and depression.

Black workers from New Orleans were 3.8 times more likely to report having lost their pre-Katrina jobs than white workers. Moreover, if these same black workers had a household income of $10,000–20,000, they were nearly twice as likely to have lost their jobs as black workers from household incomes of $40,000–50,000.

Sea level rise gave Hurricane Katrina a boost

Sea level rise and increasing storm surge risk are the clearest links between climate change and more destructive coastal storms. Rising sea levels slowly increase the chance that a storm will cause surges, even if other aspects of the storm—like wind speed—remain stable. This is because the storm, riding along higher waters, can penetrate further inland once it makes landfall. Hurricane Katrina produced the highest [8] ever recorded on the U.S. coast—an astonishing 27.8 feet at Pass Christian, Mississippi. From eastern Louisiana to Alabama, 90 miles of coastline received a storm surge characteristic of a Category 3 hurricane.[9]

A 2013 study finds that, in New Orleans, sea level rise dominates changes in flooding that are due to storm-surge by increasing mean sea level and by leading to decreased wetland area.[2] By comparing conditions on the Gulf Coast in 2005 to the climate and sea level conditions of 1900, the same study finds that Hurricane Katrina's impact would have been significantly less damaging in 1900, with a storm surge anywhere from 15 to 60 percent lower.[2]

Hurricane heat engines fueled by warm tropical waters

The intensity, [10], and duration of North Atlantic hurricanes, as well as the frequency of the strongest hurricanes, have all increased since the early 1980s, according to the US National Climate Assessment.[11] These increases are due in part to warmer sea surface temperatures in the areas where Atlantic hurricanes form and travel.

By 2100, computer models consistently show that greenhouse warming will increase the average global intensity of hurricanes by 2 to 11 percent.[12] However, there are many environmental factors that contribute to development of a tropical cyclone—including ocean water temperatures, atmospheric temperatures, air moisture levels, distance from the equator, and wind speeds and directions—making it difficult for scientists to truly predict how global warming will affect hurricanes in the long-term.

Related Content