Baton Rouge Flood August 2016

A slow-moving storm system, fed by near-record warm seas in the Gulf of Mexico and North Atlantic, began on August 7 to unleash heavy rains in the Southeastern United States. From Tuesday, August 9 through Sunday, August 14 the storm inundated Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida and Texas. Five cities in Louisiana reported rainfall totals of over two feet, with some parts of the state recording more than 20 inches of rain in 48 hours, which qualifies as a 1-in-1,000 year rainfall event. Thirteen people died in the resulting flood in what the American Red Cross called the "worst disaster since Superstorm Sandy."

Climate change about doubled the chances for the type of heavy downpours that caused the Louisiana flood, according to a climate attribution report. As the world warms, storms are able to feed on warmer ocean waters, and the air is able to hold and dump more water. On August 11, a measure of atmospheric moisture, precipitable water, was in historic territory at 2.78 inches, a measurement higher than during some past hurricanes in the region. In the Southeastern US, extreme precipitation has increased 27 percent from 1958 to 2012.

Southeastern US sees extreme rainfall, a classic signal of climate change

Beginning Sunday, August 7, a slow moving storm system headed northward from the superheated Gulf of Mexico and unleashed heavy rains on the Southeastern US, first targeting Florida's panhandle and northwestern coast. Perry, Florida, saw 4.5 inches of rain in just two hours on August 8, and Hatch Bend, Florida, reported up to 12.4 inches of rain from Sunday until 9am on Monday.[1]

Beginning Sunday, August 7, a slow moving storm system headed northward from the superheated Gulf of Mexico and unleashed heavy rains on the Southeastern US, first targeting Florida's panhandle and northwestern coast. Perry, Florida, saw 4.5 inches of rain in just two hours on August 8, and Hatch Bend, Florida, reported up to 12.4 inches of rain from Sunday until 9am on Monday.[1]

From Tuesday, August 9 through Sunday, August 14, the slow-moving storm inundated Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida and Texas.[2] Five cities in Louisiana have reported over two feet of rain, with Watson, Louisiana, topping the list at 31.39 inches.[3] The town of Lafayette, in the heart of the wettest part of the storm, reported 10.39 inches of rain on Friday, setting the town's record of wettest day until Saturday topped that at 10.40 inches.[4][5]

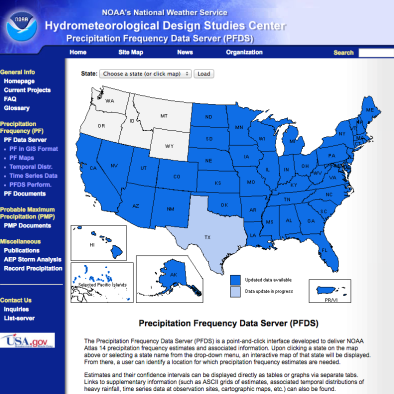

Two-day rainfall totals in Louisiana during the height of the storm were so extreme—more than 20 inches in some regions during the 48-hour period ending August 13 at 7:00 am CDT—that a National Weather Service rainfall analysis declared the storm a "1,000-year rain event."[6]

A fast-track climate change attribution study published one month after the heavy rains began found that climate change about doubled the chances for the type of heavy downpours that caused the devastating flooding in Louisiana.[7]

The global warming signal is present in these numbers. For a precipitation event of this size to occur on the central Gulf Coast, the odds have increased by at least 40 percent and most likely doubled.[8]

Karin van der Wiel, study lead, researcher and meteorologist at NOAA and Princeton University

One of the clearest changes in weather globally and across the United States is the increasing frequency of heavy rain.[9] A warmer atmosphere holds more water vapor. And like a bigger bucket, a warmer atmosphere dumps more water when it rains. The storm in the Southeastern US was supercharged by running over a warmer ocean and through an atmosphere made wetter by global warming.

Globally, climate change is now responsible for a 17 share of moderate extreme rainfall events, i.e. one-in-a-thousand day events.[10] The more extreme the event, the more likely climate change was responsible, as climate change affects the frequency of the extreme events the most. In the instance of a one-in-a-thousand year event, the odds that climate change was responsible is dramatically higher.[10]

Rivers across Louisiana are breaking flood records

Record flooding has been observed on at least ten river gauges in Louisiana.[11][12] Records are often broken when climate change and natural variability run in the same direction.

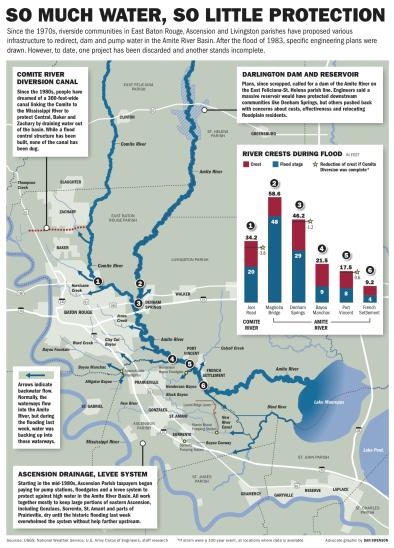

Historic flood levels along the Amite River overtopped the Laurel Ridge Levee in Ascension Paris, about 20 miles southeast of the capital of Baton Rouge, resulting in the flooding of at least 15,000 homes, or one third of the parish’s homes.[13][14]

High sea surface temperatures feed moisture and energy into storms

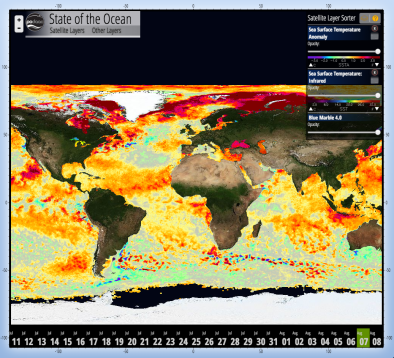

The storm system was fed by moist winds coming off the Gulf coast and North Atlantic where sea surface temperatures were running hot, bumped up by global warming. On August 7, sea surface temperatures in the Gulf hovered near 90°F (32°C) at temperatures 1.5-3.5°F above-average.[15][16][17]

The storm system was fed by moist winds coming off the Gulf coast and North Atlantic where sea surface temperatures were running hot, bumped up by global warming. On August 7, sea surface temperatures in the Gulf hovered near 90°F (32°C) at temperatures 1.5-3.5°F above-average.[15][16][17]

Along the central Gulf Coast, a measure of atmospheric moisture (from the surface up to the jet stream level) known as precipitable water is in the top percentile of historical values, often in the 2.5 to 2.75 inch range (3 to 3.5 standard deviations above normal).[12][18] In New Orleans, the precipitable water was determined to be 2.78 inches on August 10, which ranks among the top-five highest levels on record in August.[19] Precipitable water values recorded during a weather balloon launch from Slidell, LA, on August 12 were the second highest on record, ever.[15] On August 14, Lake Charles had a precipitable water reading of 2.61 inches, which is among the top-ten values on record for that station.[12]

As the world warms, storms are able to feed on warmer ocean waters, and the air is able to hold and dump more water.

Extreme rains and floods are consistent with climate change trends

Over the past century the US has witnessed a 20 percent increase in the amount of precipitation falling in the heaviest downpours, which has dramatically increased the risk of flooding.[9] Since the 1980s, a larger percentage of precipitation has come in the form of intense single-day events, and nine of the top 10 years for extreme one-day precipitation events have occurred since 1990.[20]

Over the past century the US has witnessed a 20 percent increase in the amount of precipitation falling in the heaviest downpours, which has dramatically increased the risk of flooding.[9] Since the 1980s, a larger percentage of precipitation has come in the form of intense single-day events, and nine of the top 10 years for extreme one-day precipitation events have occurred since 1990.[20]

In the Southeastern US, extreme precipitation has increased 27 percent from 1958 to 2012. Significantly, the US National Assessment reports that the long-term trend in the Southeast is larger than natural variation, an indication that changes brought on by global warming are overwhelming natural variation even at the regional level in the Southeast.[9]

Related Content