NOAA: Global warming increased odds for Louisiana downpour

Man-made climate change about doubled the chances for the type of heavy downpours that caused devastating Louisiana floods last month, a new federal study finds.

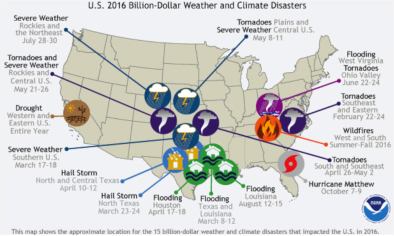

Using two different sets of measurements and computer model runs simulating thousands of years, scientists found a clear sign of global warming in the rain that triggered the flooding that killed at least 13 people, damaged 150,000 homes and cost at least $8.7 billion. More than 26 inches of rain fell in one week, with nearly a foot in just one day, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Because the downpour was less than a month ago, this study[1] - a collaboration by NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Lab, Princeton University, the Dutch weather agency and the private science-and-journalism Climate Central - has not been peer reviewed yet. Still, it has been accepted by the journal Hydrology and Earth System Sciences and will be peer reviewed live online over the next couple months. The Associated Press contacted 11 outside experts and most of them praised the science and conclusions of the study.

"The global warming signal is present in these numbers," said study lead Karin van der Wiel, a NOAA and Princeton University researcher and meteorologist. "For a precipitation event of this size to occur on the central Gulf Coast, the odds have increased by at least 40 percent and most likely doubled."

...

The scientists concluded that climate change turned a once-every-50-year situation somewhere on the Gulf to a once-every-30-year-or-less situation, and the odds of such downpours increased anywhere from 30 percent to more than 240 percent. The most likely figure is about a doubling, but van der Wiel said they can see is at least a 40 percent increase.

"We are now actually able to objectively and quantifiably say 'yes, climate change contributed to this event,'" Cullen said of the Louisiana downpours. "It's unequivocal"

Related Content