Outdated FEMA Flood Maps Don't Account For Climate Change

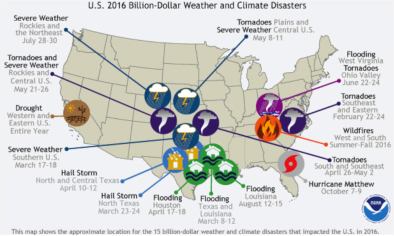

The floods that hit Louisiana last month were caused by rainfall that was unlike anything seen there in centuries. Most of the southern part of the state was drenched with up to two or three inches in an hour. A total of 31 inches fell just northeast of Baton Rouge in about three days; 20 parishes were declared federal disaster areas.

Climate scientists and flood managers suspect there could more like that to come — in Louisiana and in other parts of the country.

There have always been extraordinary rainstorms — storms stronger than anyone can remember. But Nicholas Pinter, a geologist at the University of California, Davis, who researches floods, says we shouldn't write these off as once-in-a-lifetime freak events.

"[In] our experience," Pinter says, "these kind of — call them 'acts of God explanations' — are served up just a little too easily." Sure, he says, amazing rainstorms do happen. But lately, big floods seem to be following storms more often.

"Hundred-year floods — floods of a magnitude that usually occur only once a century — [and] other large [weather] events are occurring bigger and more frequently than the published probabilities predict," Pinter says.

...

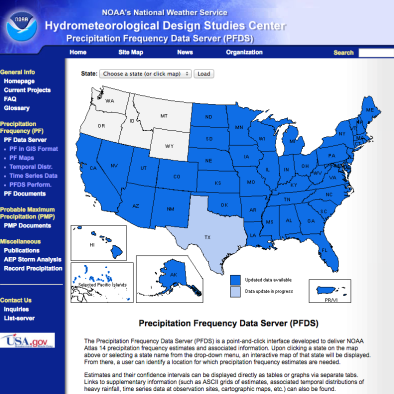

If historic rainfall data no longer hold true, that's a problem for the Federal Emergency Management Agency. FEMA draws up maps that show where flood plains are. People with federally backed mortgages in the highest risk areas have to get flood insurance. People outside those areas don't.

Kathy Schaefer is an engineer who spent 10 years drawing those maps at FEMA, and says those in use now don't take into account any rainfall changes that might have started to take place because of climate change.

"You had to ignore climate change [in drawing the maps]," she says. "All of the mapping had to be based on the existing conditions [at the time they were drawn, or many years earlier]." Those conditions were rainfall and flooding statistics from the past, she explains. Sometimes decades in the past...

Over the past couple of years, FEMA has begun to consider climate change in its flood analyses, Schaefer says. An executive order from the White House now requires it, and the agency is also proposing new operating procedures that require research into the effects of climate change on flooding.

But there's a time-lag problem: FEMA only updates its insurance flood maps every five years. Climate scientists fear that the weather may be changing faster than that

Related Content