‘We Built an App’: Keeping Track of Louisiana’s Flood-Tossed Tombs

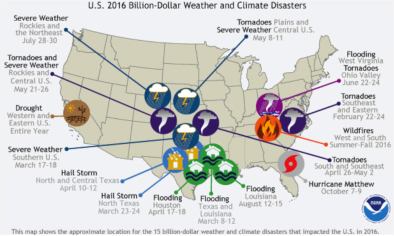

Catastrophe is the mother of invention, a lesson few other states have had to learn quite as harshly as Louisiana. With an ever-sinking coast and a front-line position for the fiercer hurricanes and other weather threats related to climate change, the state has begun to advertise itself as a disaster laboratory, a place to figure out how to combat storm surge or how to resettle imperiled communities — or how to keep track of the dead.

The occurrence of flood-tossed tombs is not a new phenomenon. Searches in the marshes after Hurricane Rita in 2005 turned up vaults that had been missing since Hurricane Audrey in 1957. But it seems to be happening with more frequency here, and, as serious coastal flooding continues to rise, it may begin to happen more frequently elsewhere, too.

So Mr. Goings and a few others — primarily Ryan Seidemann, an assistant attorney general who is familiar with the vague and complicated laws governing human remains; and Henry Yennie, a senior official at the state Department of Health in charge of tracking the hospitalized, the missing and the dead after disasters — began to informally, but seriously, consider what to do about it

Related Content