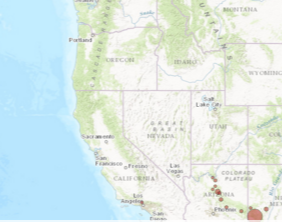

Mendocino Complex Fire July - August 2018

The Mendocino Complex—which includes the Ranch and River fires—burned 459,123 acres and was the largest fire in California state history at the time. The previous record holder, the Thomas fire, began just 8 months prior.

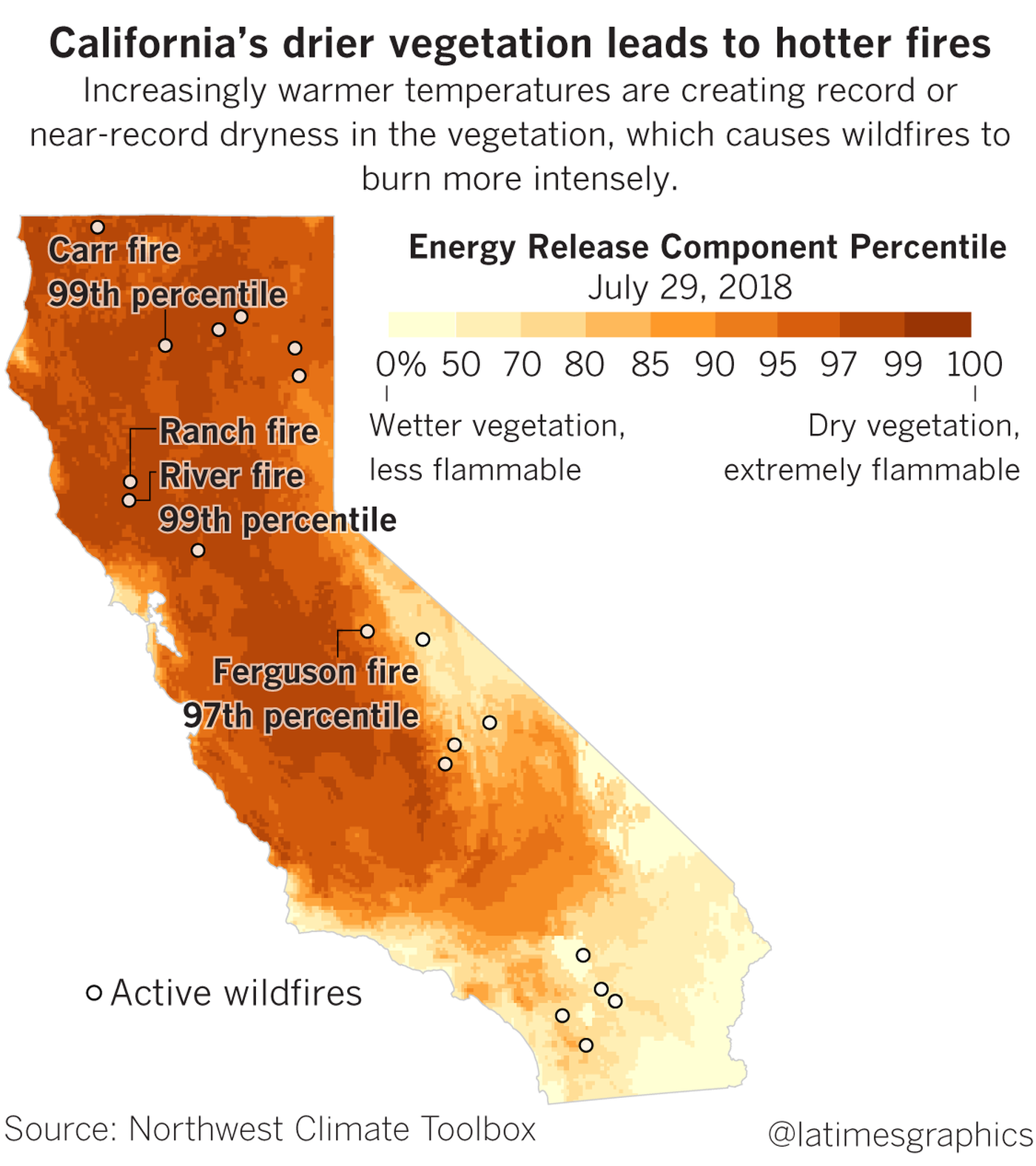

About half of the increase in recent California wildfires can be blamed on the extreme warmth fueled by human-caused climate change, according to UCLA climate scientist, Daniel Swain.[1] “The fuels . . . are just explosively dry,” Swain said, “due to a combination of low precipitation last winter, extremely high temperatures this summer and also, still, the legacy of the long-term drought.”[2]

Climate science at a glance

- Human-caused climate change is increasing wildfire activity across forested land in the western United States.[1]

- Since 1970, temperatures in the American West have increased by about twice the global average.[2]

- Scientists have found a direct link between anthropogenic warming and the observed trend of increasing heat extremes over the western US.[3]

- The effect of temperature — and how dry the vegetation is — can matter more for wildfire risk than how much rain or snow fell the previous winter.[4]

- A warmer world has drier landscapes, and dry vegetation becomes fuel for fires making them more likely to spread farther and faster.

- From 1979 to 2015, climate change accounts for 55 percent of observed increases in land surface dryness in western forests.[1]

Climate signals breakdown

Climate signal #1: Wildfire risk increase

Higher temperatures, drier conditions, increased fuel availability, and lengthening warm seasons—all linked to climate change—are increasing wildfire risk.

From 1980 to 2010, there was a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West, the length of the fire season expanded by 2.5 months, and the size of wildfires increased severalfold.[5][6]

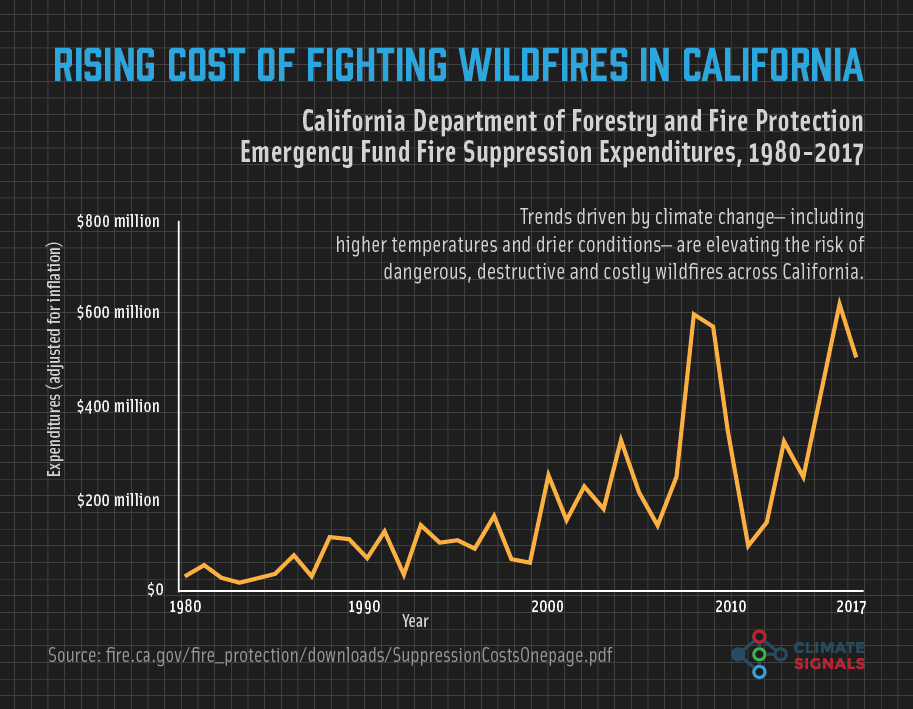

The increase in wildfire activity in California has led to an increase in the amount of money the state must spend each year to suppress wildfires, leaving less money available for fire prevention. In July, California spent more than $114 million fighting 8 fires, including the Mendocino Complex, that continued to burn into August.[7] For comparison, see the infographic below showing the rising annual cost of fighting wildfires in California.

Observations consistent with climate signal #1

- The Mendocino Complex was California's largest fire on record, having burned 459,123 acres. The simultaneously burning Carr fire near Redding, California, burned 229,651 acres and is California's seventh largest fire on record.

- Fifteen of California's 20 largest wildfires on record have burned since 2000.

- As of August 13, the Mendocino Complex destroyed 139 residences. California has experienced six of its most destructive wildfires in just 10 months.[8]

- From January 1 to August 5, 2018, CAL FIRE reported that 629,531 acres have burned in California, a figure that is still climbing rapidly with current events. This is up nearly 3 times on the same period last year and 5 times the five-year average.

Climate signal #2: Extreme heat increase

On a hot summer day, a small spark can ignite a raging wildfire. This is because when it’s hotter outside, plants dry out, lakes and streams shrink, and the ground becomes bone dry. Due to climate change, extreme heat and heatwaves are becoming more frequent. Since 1970, average annual temperatures in the western United States have increased by 1.9°F, about twice the pace of the global average warming.[2]

The fingerprint, or influence, of anthropogenic warming in the observed trend of increasing heat extremes over the western US has been formally identified.[3]

As the West heats up, conditions are primed for wildfires to ignite and spread.[2]

It is extremely fast, extremely aggressive, extremely dangerous. Look how big it got, just in a matter of days.… Look how fast this Mendocino Complex went up in ranking. That doesn’t happen. That just doesn’t happen.

Scott McLean, a deputy chief with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection[9]

When you’re really hot, a little bit hotter makes it a lot worse in terms of human health and aggravating fire danger.

Michael Wehner, senior staff scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory[16]

Observations consistent with climate signal #2

- California was record warm in July 2018 at 79.9°F. Death Valley had the hottest month of record observed anywhere at 108.1°F.

- The Mendocino Complex fires rapidly increased in size amid scorching temperatures, low humidity and windy conditions.

- Overnight on August 3-4, the Ranch Fire (one of two fires making up the Mendocino Complex) experienced "explosive growth", making a 7 to 8 mile run and adding 40,000 acres.[10]

- California temperatures were as much as 10°F higher than normal in the months leading up to the Mendocino Complex fires.[11]

- California wildfires during July 2018 burned at rates up to 20 gigawatts, i.e. the equivalent of 40 coal-fired power plants.

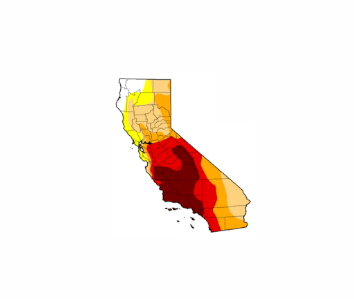

Climate signal #3: Land surface drying increase

There is a clear link between increased drought and increased fire risk.[12]

There is a clear link between increased drought and increased fire risk.[12]

Data show a direct link between climate change, surface dryness (as measured by vapor pressure deficits), and increased wildfire risk in the western United States.

- Between 2000–2015, human-caused temperature increase and vapor pressure deficit contributed to 75 percent more forested area in western US forests experiencing high fire-season fuel aridity.

- During this same period, high temperatures and VPD also added nine additional days per year of high fire potential.[1]

- In 2015-2016, human influences quintupled the risk of extreme vapor pressure deficits for western North America.[13]

- Looking further back in time, human-caused climate change accounts for 55 percent of observed increases in fuel aridity from 1979-2015 across western forests.[1]

Observations consistent with climate signal #3

- The fuels in northern California during the summer of 2018 were explosively dry due to a combination of low precipitation last winter, extremely high temperatures this summer and the legacy of the long-term drought.[14]

- Vegetation moisture in many areas in northern California were at or near-record low levels at the end of July.[15]

- A record-setting 129 million trees on 8.9 acres were dead at the end of 2017 because of the state's drought.[11]

Related Content