California Floods February 2019

On February 13 and 14, 2019, an atmospheric river storm dumped extremely heavy rainfall and snowfall across California. Parts of the state saw record rainfall, flooding and mudslides, and at least two deaths were reported.

The fingerprint of global warming has been found in the long-term trend of increasingly heavy atmospheric rivers landing on the west coast of North America.[2] More generally, climate change is driving an increase in heavy precipitation across all storm types. In California warming temperatures compound the threat of flooding, by converting snowfall into rainfall that melts snow pack and drives runoff.

Infrastructure is designed to withstand the extreme weather seen in the historical record. As extreme weather becomes more severe than weather of the past, thresholds can be crossed and infrastructure is threatened with collapse. The Oroville Dam spillway overflow in February 2017 is a good example of this pattern. An attribution study on the incident found that runoff in the watershed supplying the dam during the peak precipitation immediately prior to the damn failure was one-third greater than it otherwise would have been were it not for global warming.[1]

Science at a glance

- A warmer atmosphere drives more extreme precipitation across all storm types, which in turn increases the risk of flooding

- Atmospheric river events have been identified as the primary cause of flooding in the western United States

- The fingerprint of global warming has been found in the long-term trend of increasingly heavy atmospheric rivers landing on the west coast of North America.[1]

- Atmospheric river storms are projected to increase in intensity and duration in California in a warming climate, with the most intense atmospheric river storms becoming more frequent

- Overall conditions in California become more polarized in a warming climate, shifting toward both more drought and more flood, often alternating

- The fingerprint of global warming has already been found in one recent atmospheric river storm that broke meteorological and hydrological records in the British-Irish Isles[2]

Background information

Climate signal breakdown

Climate signals #1 and #2: Atmospheric river change and extreme precipitation increase

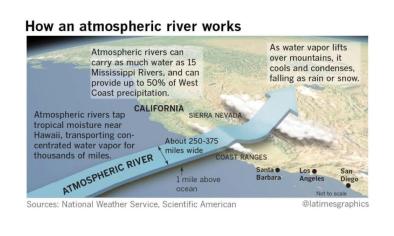

Atmospheric rivers are wide paths of moisture in the atmosphere composed of condensed water vapor. They bring extreme precipitation to land areas they pass over. They occur globally but are especially significant on the West Coast of the United States, where they create 30 percent to 50 percent of annual precipitation and are linked to water supply and problems such as flooding and mudslides.

Extreme precipitation is increasing worldwide as the warming atmosphere is holding and dumping more water when it rains. Across the United States, observational data shows an increase in the intensity and frequency of extreme precipitation events.[3]

Recent work has revealed a critical role for atmospheric rivers (ARs) in driving extreme precipitation events.[4][5][6][7] These storms drive “high‐impact hydrologic events” (HIHEs) including floods, flash floods, and debris flows.[8] In the western United States, atmospheric river events have been identified as the primary cause of flooding.[9]

In California, ARs deliver up to one-half of the state's entire annual precipitation over the course of only 10 to 15 days.[10] Between 1996 and 2007, all seven declared floods on California's Russian River were linked to atmospheric rivers.[6] A longer-term analysis showed that of 39 declared floods on the Russian River since 1948, 87 percent were caused by atmospheric rivers.[11] A July 2015 study found that climate change may increase horizontal water vapor transport by up to 40 percent in the North Pacific, due mainly to increases in air moisture.[12]

An August 2017 study spanning seven-decades of data revealed a trend in increasingly heavy land-falling atmospheric rivers driven by a long-term warming of the North Pacific, which sends more water vapor to North America.[1]

High-resolution climate models report that atmospheric storms linger and become more intense in a warming climate. In addition, the models project that these storms will land more frequently in Southern California.

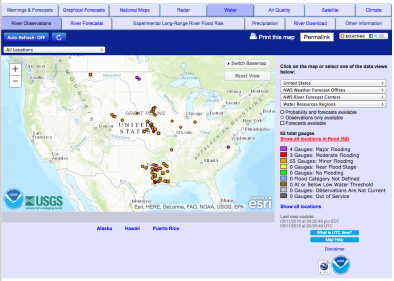

Observations consistent with climate signals #1 and #2

- The storm was classified as a Category 3 ("strong") on the Ralph Scale, which assesses atmospheric rivers based on intensity and duration.[13]

- On February 13, downtown Sacramento set a new daily rainfall record of 1.94 inches (2.54 cm).[14]

- Palm Springs had its wettest February day on record, with 3.68 inches on February 14.[13]

- Over a foot of snow fell on Redding — more than that city had seen in half a century.[13]

- On February 14, several sites in Southern California set daily rainfall records, and one of those — Palomar Observatory — had its wettest day ever recorded, with 10.1 inches (25.65 cm) falling in 24 hours.[15]

Climate signal #3: Rapid Snowpack Melt

Global warming affects snow and ice cover by increasing the amount of precipitation falling as rain instead of snow and by hastening snowmelt. Scientists have already observed these trends in the Western US.

California has experienced climate change-amplified loss of snowpack due to higher temperatures that are accelerating spring melt and increasing the amount of precipitation falling as rain instead of snow.[16] During the 2014-2015 water season—and for the first time in 120 years of record keeping—the winter average minimum temperature in the Sierra Nevada was above freezing, helping to explain the season’s record-low snowpack.[17]

The risk with an atmospheric river storm is that large volumes of relatively warm water falling on snowpack can cause snow to melt early, contributing to flooding at lower elevations and depleting California's summer and fall water supply. (In normal years, snowpack provides about a third of the state’s total water supply.)[18]

Climate signal #4: Runoff and flood risk increase

More intense rainfall events and regional increases in precipitation linked to climate change are increasing the risk of extreme runoff and flooding in some locations. Precipitation is a major driver for river discharge trends and for changes across annual and decadal time scales.

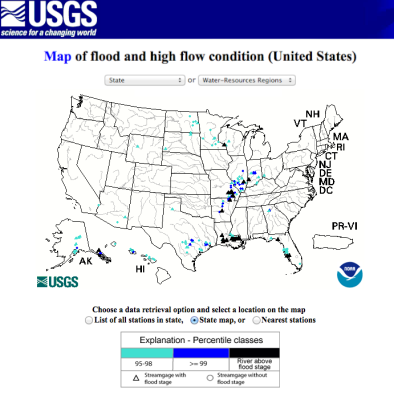

Observations consistent with climate signal #4

Related Content