North American Moose Decline 2006 -

Moose decline across the northern US—from Montana to New Hampshire—is intensifying due to exploding tick populations, rising temperatures, shorter winters, and flourishing white-tailed deer and their parasites. At the root of these problems could be something much harder to control: climate change.

Dramatic moose decline signals global warming threat to wildlife

Moose decline has intensified in recent years, with species (Alces alces) found across several states in the northern US—from New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine to Minnesota, Michigan and even Montana—dying at an alarming rate. The population in northeast Minnesota went from 8,840 in 2006 down to only 2,760 in January 2013.[1]

While the 2016 aerial moose survey estimates the population has grown to 4,020, Glenn DelGiudice—the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources moose project leader—warned, “Moose are not recovering.”[2] DelGiudice continues saying, “It's encouraging to see that the decline in the population since 2012 has not been as steep, but longer term projections continue to indicate that our moose population decline will continue.”

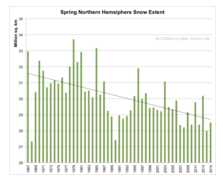

Scientists attribute most of this decline to increasing temperatures

The northern US is at the very southern boundary of the North American moose population's range.[3] This means even a small amount of warming can push the North American moose—animals adapted for extreme cold—past a critical threshold, causing changes in their physiology and behavior.[4]

When it gets too warm, moose will seek shelter instead of foraging for the food necessary to stay healthy.[5] Studies have shown that chronic exposure of moose to high ambient temperatures has been correlated with lower survival in northeastern Minnesota.[6]

Shorter and warmer winters produce parasite proliferation

Warmer temperatures, in addition to compromising moose health, are beneficial to some of the parasites that plague the moose. Warmer temperatures favor the spread of brainworm and liver flukes, parasites spread to moose by white-tailed dear—a species growing in population as the moose declines.[7] Researchers are most concerned, however, about the proliferation of winter ticks.

The lifecycle of ticks found on moose would typically go like this: in the autumn, ticks latch onto moose where they remain until March or April at which time they fall off—landing on ground that is still cold and snow-covered—and die.[8] However, if the winter is shorter and warmer, ticks are more likely to fall on warm, bare ground, which allows female ticks to lay eggs and repeat the cycle, causing tick populations to boom.[9]

Studies have shown that tick infestations on northern US moose populations average 33,000 ticks per moose, with some individuals carrying up to 100,000 ticks.[8] In such high quantities, the ticks can cause anemia and extreme irritation, leading the animals to scratch off areas of fur, which then makes them vulnerable to the winter cold and infection.[8] Moose with large patches of broken hair are sometimes referred to as “ghost” moose because the white base of the hair shaft is all that remains (see image on the right).