Hurricane Sandy 2012

Hurricane Sandy illustrated several different ways in which climate change can increase storm damage. Primarily, sea level rise increases the reach of storm surge, a warmer atmosphere can hold and dump more precipitation, and warmer sea surface temperatures increase the maximum potential intensity of the storm. The storm was the second most costly US hurricane on record, after Katrina, and caused 159 deaths. Sandy was fueled by sea surface temperatures 5.4°F above average and veered into New Jersey and New York atop sea levels elevated by global warming.

Hurricane Sandy devastated coastal communities from Jamaica to Canada

Hurricane Sandy was the most intense hurricane on record to make landfall north of Cape Hatteras, consistent with poleward expansion of the zone for strong hurricanes.

When hurricane hunter aircraft measured its central pressure at 940 millibars — 27.76 inches — Monday afternoon, it was the lowest barometric reading ever recorded for an Atlantic storm to make landfall north of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.

Waters off the Northeastern coast, where Sandy strengthened before veering northwestward toward New Jersey, were 5.4°F (3.0°C) above average.

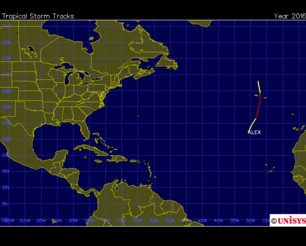

Hurricane Sandy first made landfall as a category 1 hurricane in Jamaica, then as a category 3 hurricane in Cuba. It weakened to a category 1 crossing the Bahamas and moved along the southeastern coast of the United States, where it finally veered northwestward toward the mid-Atlantic states making landfall as a post-tropical cyclone near Brigantine, New Jersey.

Hurricane Sandy first made landfall as a category 1 hurricane in Jamaica, then as a category 3 hurricane in Cuba. It weakened to a category 1 crossing the Bahamas and moved along the southeastern coast of the United States, where it finally veered northwestward toward the mid-Atlantic states making landfall as a post-tropical cyclone near Brigantine, New Jersey.

As it tracked northward, Sandy was responsible for at least 159 direct deaths[1], with an estimated 72 of these fatalities occurring in the mid-Atlantic and Northeastern US.[2] Storm surge was responsible for most of the US deaths, with 41 of the 72 fatalities (or 57 percent) attributable specifically to that hazard.[2]

The second most costly Hurricane in US history

Damages—concentrated in New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut—were estimated at $67.6 billion, making Sandy the second most costly Atlantic Hurricane in history behind Katrina.[1] It is also estimated that 650,000 homes were damaged or destroyed, and that 8.5 million people were without power.[2]

Floodwaters inundated subway tunnels in New York City, and the New York Stock Exchange closed for two consecutive business days, which last happened in 1888 due to a major winter storm.[2] Sandy also caused significant damage to the electrical grid and overwhelmed sewage treatment plants

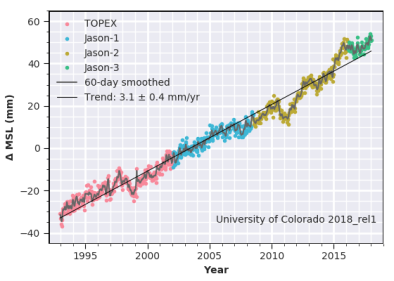

Sea level rise fuels storm surge and flooding

Hurricanes now ride atop elevated sea levels, contributing to storm surge and flooding, the leading cause of hurricane storm damage and fatalities.

Climate-change related increases in sea level have nearly doubled today’s annual probability of a Sandy-level flood recurrence as compared to 1950.[3]

Global warming fuels heavier rains and stronger storms

The intensity, frequency, and duration of North Atlantic hurricanes, as well as the frequency of the strongest hurricanes, have all increased since the early 1980s, according to the US National Climate Assessment.[4] Global warming heats up sea surface temperatures which in turn fuel storms.

Global warming also concentrates rainfall into extreme events. A warmer atmosphere holds more water vapor, and dumps more precipitation when it does rain, much like a larger bucket holds and dumps more water.

During September 2012, the month preceding Hurricane Sandy, the combined land and ocean surface global surface temperature anomaly was the warmest on record, 1.21°F (0.67°C) above the 20th century average. Waters off the Northeastern coast, where Sandy strengthened before veering northwestward toward New Jersey, were 5.4°F (3.0°C) above average.[5] These conditions likely contributed to the storm's intensity and rainfall.

Related Content