The economic costs of Hurricane Harvey attributable to climate change

Study key findings

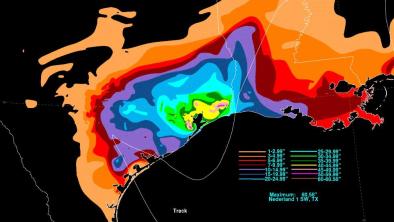

- $67 billion of the damages caused by Hurricane Harvey – which made landfall in Texas and Louisiana in August 2017 – is attributable to human-caused climate change

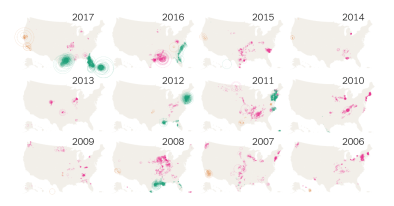

- The research develops a new way of combining climate science with the economics of natural disasters.

- The results indicate that the “fraction of attributable risk” for the rainfall from Harvey was likely about at least a third with a preferable/best estimate of three quarters

- Applying this fraction to the average estimate of damages from Harvey assessed at about US $90 billion gives a best estimate of US $67 billion, with a likely lower bound of at least US $30 billion

Study abstract

Hurricane Harvey is one of the costliest tropical cyclones in history. In this paper, we use a probabilistic event attribution framework to estimate the costs associated with Hurricane Harvey that are attributable to anthropogenic influence on the climate system. Results indicate that the “fraction of attributable risk” for the rainfall from Harvey was likely about at least a third with a preferable/best estimate of three quarters. With an average estimate of damages from Harvey assessed at about US$90bn, applying this fraction gives a best estimate of US$67bn, with a likely lower bound of at least US$30bn, of these damages that are attributable to the human influence on climate. This “bottom-up” event-based estimate of climate change damages contrasts sharply with the more “top-down” approach using integrated assessment models (IAMs) or global macroeconometric estimates: one IAM estimates annual climate change damages in the USA to be in the region of US$21.3bn. While the two approaches are not easily comparable, it is noteworthy that our “bottom-up” results estimate that one single extreme weather event contributes more to climate change damages in the USA than an entire year by the “top-down” method. Given that the “top-down” approach, at best, parameterizes but does not resolve the effects of extreme weather events, our findings suggest that the “bottom-up” approach is a useful avenue to pursue in future attempts to refine estimates of climate change damages.

Related Content