The science of warmer winters: Sierra temps rising faster, greater impact on snowpack

Trends of warmer winter temperature in the Sierra Nevada are predicted to reduce local snowpack — western Nevada County’s most important source of water.

In the future, precipitation increasingly will fall as rain instead of snow, scientists forecast.

The impact of that shift on local water supply is dramatic. Nevada Irrigation District’s system for collecting water for local use — like other systems along the Sierra Nevada — was built on the assumption that wintertime precipitation would come as snow and stay in the mountains until the spring melt. That snowmelt, further, would come as temperatures warm and rains subside, refilling reservoirs and providing a cushion going into the next year.

In the watershed supplying NID, this frozen reservoir holds about 125,000 acre-feet of water, or about what NID customers use in a typical year. It is predicted to shrink by nearly half within 30 years, according to climate models.

It was the combination of both low precipitation and high temperatures that led to this severe drought." – Soumaya Belmecheri, University of Arizona

Many scientific studies document what is happening in the Sierra Nevada and forecast the future:

- Average wintertime (December-January-February) low temperatures have risen 2.02 degrees Fahrenheit across the Sierra Nevada over the last 123 years, according to weather data collected by the Western Regional Climate Center, in Reno. That rise takes into account the big warm-and-cool cycles seen in the last century.

- Average wintertime low temperatures are the key to forming and keeping snowpack. They are warming faster than average highs, according to the California Department of Water Resources.

- Most winters since 2000, the average wintertime temperatures in the Sierra Nevada have been warmer than the historical average of 26 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Climate Center data.

- Warmer temperatures have pushed the snowline above the historic Sierra average of roughly 6,775 feet elevation for most winters since the mid-1990s, said Climate Center regional climatologist Daniel McEvoy.

- Precipitation hasn’t changed much over many of those years. So, precipitation falls more often as rain, and less snowpack forms.

“There have been more warm years and fewer cold years since 2000,” McEvoy said. “If it were colder, that precipitation would have been stored in snowpack.”

7 degrees warmer by century’s end

Dry years already come naturally and frequently to California. But higher temperatures also mean dry years, like the drought from 2012 through 2015, will grow drier and come more often, scientists predict.

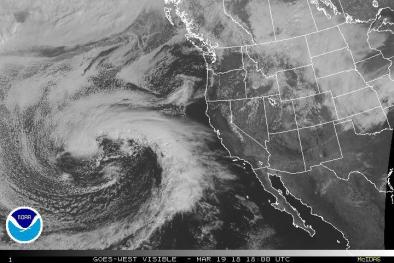

- Since 1975, warmer years in the Sierra Nevada come more frequently than before that time, according to data from the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration.

- As a result, California more often gets several warm years in a row, instead of two or three warm years followed by a cooler year, according to Climate Center data. The clumping of hot, dry years, of course, makes it harder for ecosystems and human-engineered water systems to recover, scientists have noted.

This latest clump of four record-dry years (in northern California) coincided with two record-warm years.

“What was different (about this drought) was the temperature was very high,” explained Soumaya Belmecheri, of the University of Arizona’s Laboratory of Tree Ring Research. “It was the combination of both effects (low precipitation and high temperatures) that led to this severe drought condition.”

If greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current pace, Sierra Nevada temperatures are projected to rise by the end of this century as much as 7 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit, depending on the month, above the average temperatures measured from 1981 to 2000. That’s according to a study released in March by researchers Neil Berg and Alex Hall, of the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles. They are part of UCLA’s Institute for Environment and Sustainability.

Related Content