Snowpack Near Record Lows Spells Trouble for Western Water Supplies

Months of exceptionally warm weather and an early winter snow drought across big swaths of the West have left the snowpack at record-low levels in parts of the Central and Southern Rockies, raising concerns about water shortages and economic damage.

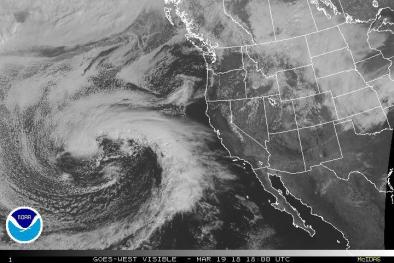

Drought spread across large parts of the Western United States this month, and storms that moved across the region in early January made up only a small part of the deficit. Runoff from melting snow is now projected to be less than 50 percent of average in key river basins in the central and southern Rockies.

Most of the region's annual water cycle starts as thick layers of mountain snow that accumulate during winter and melt slowly in spring. If the snows don't come, there's no water to fill the reservoirs.

A series of recent studies examines how vulnerable that snowpack is to rising temperatures, and how the economic costs from the declining snowpack could soar into the hundreds of billions of dollars.

...

How Sensitive Is Snow to Climate Change?

University of Colorado hydrologist Keith Musselman's research in the southern Sierra Nevada shows how sensitive mountain snowpack is to global warming. Analyzing an extensive dataset from the western flank of the Sierra, he found that the snowpack shrinks by 10 percent for every 1 degree Celsius of warming. And winter rain storms will increase as global temperatures rise, melting snow that's already piled up and raising flood risks.

The middle elevations of the mountain range are most sensitive, Musselman found, standing to lose about 40 percent of their snowpack if average global temperatures rises by 2 degrees Celsius in the next few decades, and 50 percent at 3 degrees Celsius warming, a temperature increase that seems increasingly likely by the end of the century unless global greenhouse gas emissions start dropping quickly.

Climate scientists say snow seasons like the West is experiencing now will become more common in the next few decades. If winter snows don't come, there won't be much water to fill the reservoirs, potentially leaving cities like Las Vegas, Phoenix and Los Angeles dry in the future.

The changes may come faster than expected, according to Oregon State University climate scientist Philip Mote, referring to a Nov. 2017 studyshowing how the snow line—the elevation where rain changes over to snow—in California's northern Sierra Nevada raced uphill by as much as 236 vertical feet per year between 2008 and 2017, the warmest decade in Earth's observed climate history.

If the same trend continues in the coming years, water managers will have to make extensive—and expensive—adjustments to water storage and distribution.

"Warming background temperatures combined with changes from snow to rain leads to decreased water availability in spring and throughout the warm season," the study's authors concluded.

Related Content