Why Is Oklahoma Burning?

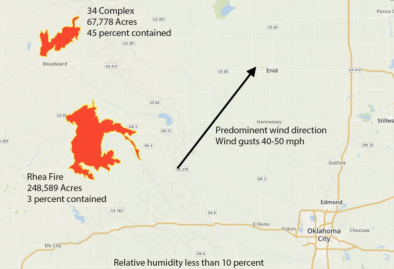

Oklahoma’s third megafire in three years—the Rhea Fire, which has torched some 242,000 acres in less than a week—may grow even worse on Tuesday, as horrific fire weather conditions sweep in from New Mexico and west Texas.

...

Weather, climate, vegetation: How they’re conspiring to bring megafires to Oklahoma

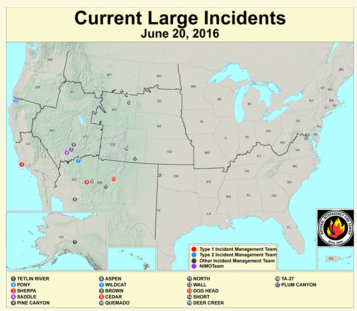

It seems that every year in Oklahoma now brings a megafire—defined by the National Interagency Fire Center as a wildfire that consumes more than 100,000 acres.

In March 2016, it was the Anderson Creek Fire, which raced across the Oklahoma/Kansas border and torched a total of nearly 400,000 acres. (Even though only part of the fire was in Kansas, it still qualified as that state’s largest on record.)

March 2017 brought the even-more-massive Northwest Oklahoma fire complex, which devoured more than 830,000 acres.

...

The recent spate of Oklahoma megafires isn’t the work of a single villain; it’s more of a team effort. State climatologist Gary McManus helped me wrap my brain around this emerging threat to the state’s land, people and economy. McManus identified several factors at work:

—Unusually serious fire weather. The sun-baked, wind-whipped Oklahoma landscape can dry out quickly in late winter or early spring. All it takes at that point is a day or two of extreme fire weather, and the main components are simple: strong winds and very low relative humidity (RH). You’ll often see very high temperatures accompanying these two, because dry air that flows downslope from the Southern Rockies, or that descends on the south side of a major spring storm system, warms up as it heads toward Oklahoma.

...

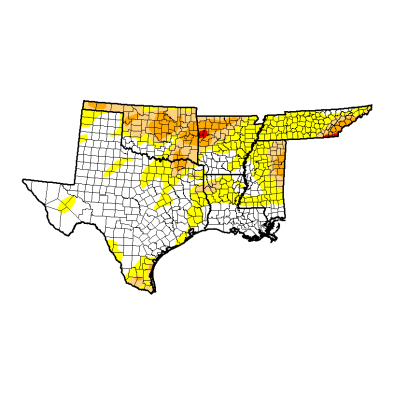

—Alternating wet and dry periods leading to a profusion of fire-prone vegetation.

Echoing a global trend that’s associated with human-produced climate change, Oklahoma has seen signs of a ramp-up in hydrologic extremes over the past few years.

May 2015 was the state’s wettest single month on record, and 2015 was its wettest year. “The November-December 2015 period was the wettest on record as well, and the sixth warmest. So the growing season extended into winter to some extent that year,” said McManus. The result was an unusually lush landscape going into the first part of 2016 that dried out quickly in the weeks leading up to the Anderson Creek fire.

Related Content