Understanding climate: Antarctic sea ice extent

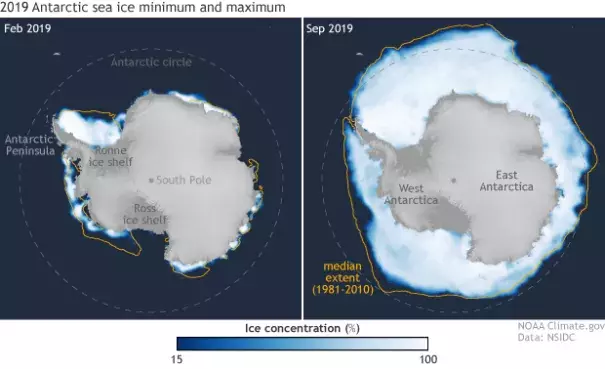

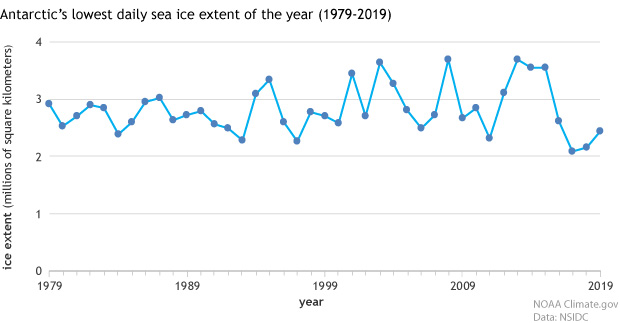

As it does in the Arctic, the surface of the ocean around Antarctica freezes over in the winter and melts back each summer. Antarctic sea ice usually reaches its annual maximum extent in mid- to late September, and reaches its annual minimum in late February or early March. The start of 2019 brought the lowest Antarctic sea ice extent on record for that time of year, but although the 2019 minimum extent (on February 28, 2019) was well below the 1981–2010 climatological average, it was not a record low.

The sea ice satellite record dates back to October 25, 1978. Unlike the Arctic, where sea ice extent is declining in all areas in all seasons, Antarctic trends are less apparent. From 1979–2017, Antarctic-wide sea ice extent showed a slightly positive trend overall, although some regions experienced declines. Those exceptions have occurred around the Antarctic Peninsula. The region south and west of the Antarctic Peninsula has shown a persistent decline, but this downward trend is small compared to the high variability of Antarctic sea ice overall. Another region near the northern tip of the Peninsula, in the Weddell Sea, showed strong sea ice declines until 2006, but the ice in that region has rebounded in recent years.

...

Land-sea configurations affect sea ice extents not only by limiting where ice can form, but also by introducing their own effects. In the Arctic, landmasses surround and influence the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean. Ice and (especially) snow are highly reflective, bouncing much of the Sun’s energy back into space. As Northern Hemisphere spring and summer snow cover declines, the underlying land surface absorbs more energy and warms. Warmer conditions on land affect the nearby ocean, and more sea ice melts as a result. The melt-warmth-melt feedback cycle means that the Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the globe.

No such polar amplification effect has occurred on a large scale in the Southern Hemisphere, however. Antarctica is surrounded by ocean, not a land surface that is losing its reflective snow and ice cover in the spring and summer. It was already normal, historically, for summertime sea ice to melt back nearly to the Antarctic coastline, leaving large expanses of the Southern Ocean exposed to heating from the summer sun. By contrast, the loss of reflective snow and ice in high northern latitudes surrounding the Arctic Basin represents a profound change from what was historically normal.

Where sea ice does melt away completely in the Antarctic summer, the ice’s absence can have cascading effects. For example, sea ice retreat in the Weddell Sea along the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula probably contributed to Larsen Ice Shelf losses. Ice shelves—thick slabs of floating ice attached to coastlines and usually fed by glaciers—fringe the frozen continent. Intact sea ice in front of an ice shelf buffers the shelf from ocean swells. When the ice is gone, ocean waves can flex the shelf and make it more vulnerable to disintegration. Depending on how much an ice shelf disintegrates, the glacier feeding it may accelerate into the ocean. But sea ice retreat alone rarely, if ever, initiates the disintegration process; other factors such as warm ocean water and surface melt on the ice shelf are usually at work, too.

ant

Related Content