As temperatures rocket, cities fight heat waves

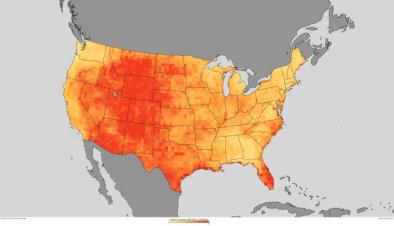

This summer alone, extreme heat has killed grape pickers in California fields and hikers in Arizona. At least four people died of heat-related illnesses in El Paso, Texas, where the city saw 16 days in a row of temperatures exceeding 100 degrees, the third-longest stretch ever. Phoenix saw its hottest combined June and July on record, with temperatures averaging 96 degrees daily. And higher-than-average temperatures and drought have scorched corn and peanut crops in Tennessee and Georgia.

...

People who respond to heat waves are especially alarmed by a specific climate change trend: the rise in nighttime lows in some places during the summer.

In many cities, temperatures aren't cooling at night in the summer the way they once did. In Washington, D.C., this summer, for example, the temperature stayed at 70 degrees or above at night for 35 days straight in July and August, a record in 145 years of record-keeping, The Washington Post reported.

"When we look at how extreme heat affects our health, we see the most impacts when we have multiday events and when nighttime temperatures don't cool off enough to give us a respite," said Katharine Hayhoe, director of Texas Tech University's Climate Science Center.

"So when we don't get a break, when those daytime highs just keep getting higher and higher, and when it doesn't cool off enough at nighttime, that's when we start to see impacts on our health," she said.

Such a trend means people can expect less relief from cooler air at night in the summer, a worrisome climate shift where people rely on cooler nighttime temperatures to ease the discomfort of the day. That's especially crucial in some parts of the Midwest or Pacific Northwest, where air conditioning isn't as common.

There are studies that show the cooling needs of the body are most crucial at nighttime, said Shalini Gupta, executive director of the Center for Earth, Energy and Democracy in Minneapolis. Yet few cities have taken that into consideration with their planning. Cooling centers may not be open at night — and malls and other public facilities open to people during the day are also closed.

Cities could be doing a better job of planning more comprehensively, said Cecilia Martinez, director of research programs at CEED.

"A lot of cities have climate action plans in terms of mitigation," she said. "More are developing climate adaptation plans. But we still need much more work on climate action plans or climate resiliency plans that can address the climate impact of heat waves."

...

Climate-change-fueled heat waves are a major worry at all levels of government, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has as its guiding philosophy on heat waves that any death connected to the temperature is preventable. Heat waves of long duration are especially harmful, said George Luber, an epidemiologist who heads the Climate and Health Program at the CDC.

"What we do know is the high risk is during periods of time when the temperature is anomalously high," Luber said. "Hot days aren't enough. It's got to be anomalously high. What we know with climate change is the occurrence of anomalously hot days will increase."

To be sure, heat waves are a normal part of U.S. summers, Katharine Hayhoe, director of Texas Tech University's Climate Science Center, said during a news conference at the height of a July heat wave to discuss how climate change alters how cities should plan for heat events.

Yet as the earth warms and the climate becomes less stable, she said, it's more difficult to use past heat events "to predict what we need to prepare for in the future."

"It's changing quite rapidly; it's changing faster than we've ever seen climate change in the history of human civilization on this planet," Hayhoe said. "And that is really the key to why this matters. It matters because of us. We are adapted to the climate that we're used to in the past. But when climate changes, we are not adapted to that. We are not used to having heat waves that are as extreme as the ones we see today."

Hayhoe said climate scientists get asked the same question with nearly every heat wave: Is it caused by climate change or not?

"The answer is: It's both," she said. "We get heat waves naturally, but climate change is amping them up, it's giving them that extra energy, that extra heat to make them even more serious and give them even more impacts"

Related Content