'A prisoner of environment': is it time to leave the American west?

Maricela Ruelas is a manager at a vineyard in Medford, Oregon. She trims, harvests – whatever needs doing. This year, she has done much of that work in a face mask.

Wildfire smoke has plagued her and her fellow workers nearly continuously for “a couple of months”, she said through a translator, leading to pounding headaches. “It was horrible, horrible this year.”

For Ruelas, the smoke isn’t just a nuisance; it’s an economic hardship. She and her co-workers are paid by the hour, so when they have to leave work early because their heads and lungs hurt, they don’t get paid. And Ruelas sends less money home to her grown children in Guadalajara.

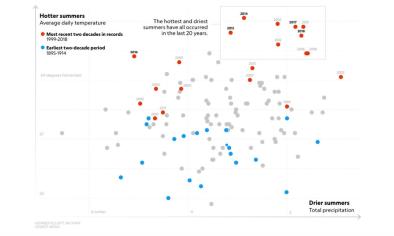

The west is drier, hotter than ever, frequently on fire. Thanks to reduced snowpacks in the mountains, the soil is parched by early summer and forests are tinder. What firefighters once called a “fire season” is now referred to as a “fire year”, since the fires start so early and rage deep into fall.

These extreme phenomena are causing some people to consider leaving the western US, a place long conceptualized in the American imagination as the land of balmy weather and fresh starts. Some have already left. They are sick of wildfire smoke; worried that a lack of water will destroy their communities or about climate migrants from other parts of the country; and struggling with the heat itself.

“I felt bad leaving people behind who don’t have that ability to uproot,” said Michael Lakeman, a New Zealander who moved with his American wife and kids back to his home country from Seattle this summer.

Related Content