How Warming Winters Are Affecting Everything

Climate Signals Summary: Climate change is increasing temperatures in all seasons, including winter, and this has a variety of consequences. Warm winters can lead to snowpack decline, vector-borne disease increase, sea ice decline, and more precipitation falling as rain rather than snow, just to name a few.

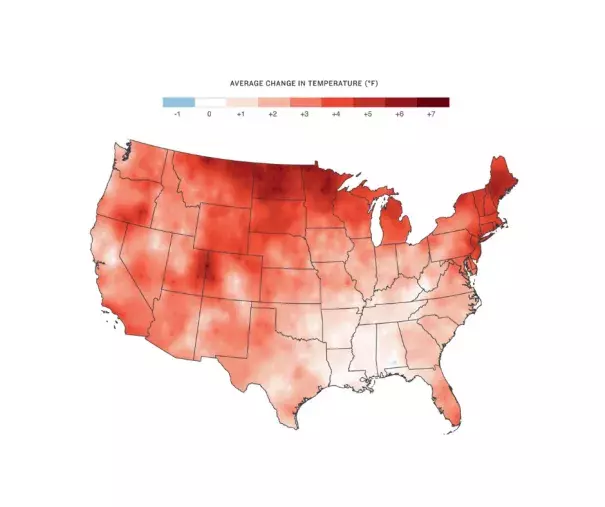

Article Excerpt: Winters are warming faster than other seasons across much of the United States. While that may sound like a welcome change for those bundled in scarves and hats, it's causing a cascade of unpredictable impacts in communities across the country.

Temperatures continue to steadily rise around the globe, but that trend isn't spread evenly across the map or even the yearly calendar.

"The cold seasons are warming faster than the warm seasons," says Deke Arndt, chief of climate monitoring at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Centers for Environmental Information. "The colder times of day are warming faster than warmer times of day. And the colder places are warming faster than the warmer places."

...

The nation's largest economy and largest agricultural industry is heavily reliant on snow that falls high in the Sierra Nevada, which acts like a giant reservoir. The snowpack lasts through the winter and melts in late spring and early summer, sending a steady supply of water to farms and cities when they need it most.

But with warming temperatures, California's snowpack is shrinking, both because of increased snowmelt and because more precipitation is falling as rain instead of snow. Across the West, snowpack has already shrunk by 15% to 30%.

...

Warmer winters are also affecting the fruits and vegetables that California sends around the country. The state produces the majority of the country's supply of almonds, wine grapes, walnuts, pistachios and peaches. But many of those crops require a certain amount of cold weather, what's known as "chill hours." Without that, pollination can be delayed or incomplete, reducing the crop that farmers get at harvest time.

...

For decades, the Southeast actually got cooler while the rest of the country warmed. But now it's warming too, and that includes winters, with the length of the freeze-free season increasing in some places by as much as a week and a half.

That's a problem for farmers, who need cold temperatures for their plants to set fruit. The winter of 2016-2017 was too warm for Georgia peaches, for instance, and about 80% of the crop failed.

...

"Warmer winters will result in, usually, earlier emergence of adult mosquitoes, for example, that bite us earlier in the springtime. It means that larger populations will survive throughout the winter," says Duke University professor Bill Pan, who studies environmental change and disease.

It's already warm enough in the South for the mosquito species that can carry dengue, chikungunya and Zika. In some parts of Florida, the mosquitoes can be active year-round. According to the latest National Climate Assessment, dengue cases could go up across the Southeast in the summer, and West Nile will likely increase too.

...

Warmer winters have also helped fuel the expansion of a pest that affects outdoor enthusiasts throughout the year: ticks.

Deer ticks transmit several diseases, including Lyme, which has grown from a few hundred cases in Maine more than a decade ago to a high last year of more than 2,100. Cases of another tick-borne disease, anaplasmosis, have also surged in the state to more than 680, up from just single cases in the early 2000s.

...

Despite the occasional polar vortex that can send temperatures plunging well below zero, generally warmer Midwest winters have implications from agriculture to recreation.

"We talk about this all the time," says Dennis Todey, director of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Midwest Climate Hub, in Ames, Iowa.

...

The most visible impact of warming winters in the Mountain West is on the forests. Millions of trees have died from pine, spruce and pinyon ips bark beetles over the past three decades.

Normally, bark beetles die off in freezing temperatures. "When you have periods of temperature that do not reach the lethal level for the insects, that's when you start seeing increased survival of the population," says Jose Negron, a research entomologist with the U.S. Forest Service.

...

Bats play a key role in agriculture, helping to control pests and to fertilize and pollinate some crops. Changing migration patterns could also hurt crops that depend on them, creating what scientists call a "mismatch."

Researchers are seeing more mismatches as a result of climate change, says Norma Fowler, a biology professor at the University of Texas at Austin. "You can get plants that bloom before the pollinators are available," she says. "You can get birds that come north before the insects are out for them to eat."

...

On Alaska's western coast, thick winter sea ice has long protected remote villages from storms. But that ice cover has been freezing later and shrinking to record lows, allowing strong waves to eat away at land made fragile by thawing permafrost. After years of struggle, the village of Newtok late last year started moving residents to safer ground farther inland.

Inupiat on Alaska's North Slope use sea ice as a platform from which to hunt bowhead whales and walruses. Diminished ice in the Arctic is making those harvests more difficult.

Related Content