Here's what we've learned about hurricanes since Sandy

When hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria recently pounded Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico, the severity of the storms was often attributed to climate change. “Four Underappreciated Ways That Climate Change Could Make Hurricanes Even Worse,” was the headline in the Washington Post; “Hurricane Harvey’s Size and Impact Points to Climate Change,” noted NPR.

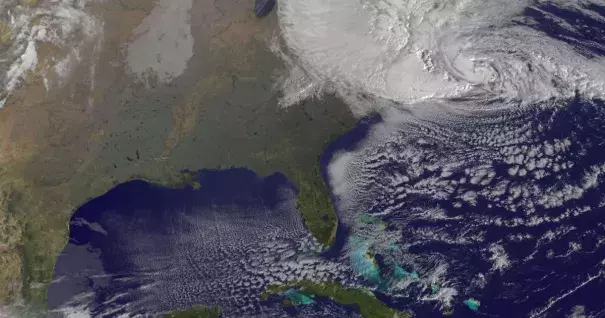

But five years ago, when Superstorm Sandy took its famous left turn to barrel into the East Coast, there was no such certainty. Instead, a debate played out in the media and on Twitter about whether it was fair to blame climate change for the storm’s intensity.

One reason why the conversation has changed is that the science has become much more advanced, especially in the field of attribution science—a relatively new discipline within climate science that looks at how climate change factors into individual weather events. During Hurricane Katrina in 2005, attribution science was in its “infancy,” one scientist told the Post, and even when Sandy hit, the dominant narrative was that climate change doesn’t necessarily affect individual extreme weather events. But today, both the computer models and how scientists have learned to communicate the lessons of climate science have become more sophisticated, and there is a growing body of peer-reviewed published literature on the subject, though not without some controversy.

No one suggests that climate change caused a single weather event, but scientists have grown a lot more comfortable talking about the ways rising temperatures affect extreme weather, creating the right conditions to fuel wetter storms and bigger, more dangerous storm surges.

Related Content