EXPLAINER: Topsy-turvy weather comes from polar vortex

Climate Signals Summary: There are three things to consider when squaring this extreme winter weather with climate change: cold weather doesn’t cancel out decades of warming; rapid Arctic warming is associated with disruptive winter weather in the US; and cold events aren’t as cold as they would have been without climate change.

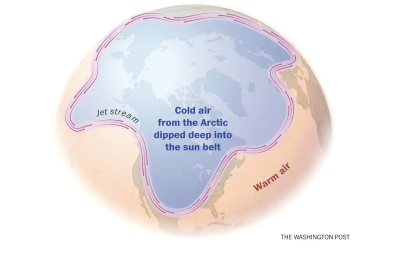

Article Excerpt: Around the North Pole, winter’s ultra-cold air is usually kept bottled up 15 to 30 miles high. That’s the polar vortex, which spins like a whirling top at the top of the planet. But occasionally something slams against the top, sending the cold air escaping from its Arctic home and heading south. It’s been happening more often, and scientists are still not completely sure why, but they suggest it’s a mix of natural random weather and human-caused climate change.

This particular polar vortex breakdown has been a whopper. Meteorologists call it one of the biggest, nastiest and longest-lasting ones they’ve seen, and they’ve been watching since at least the 1950 s. This week’s weather is part of a pattern stretching back to January.

“It’s been a major breakdown,” said Jennifer Francis, a climate scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center on Cape Cod. “It really is the cause of all of these crazy weather events in the Northern Hemisphere.”

“It’s been unusual for a few weeks now — very, very crazy,” Francis said. “Totally topsy-turvy.”

...

Several meteorologists squarely blamed the polar vortex breakdown or disruption.

These used to happen once every other year or so, but research shows they are now close to happening yearly, if not more, said Judah Cohen, a winter storm expert for Atmospheric Environmental Research, a commercial firm outside of Boston.

...

The polar vortex spends winter in its normal place until an atmospheric wave — the type that brings weather patterns here and there — slams into it. Normally such waves don’t do much to the strong vortex, but occasionally the wave has enough energy to push the spinning top over, and that’s when the frigid air breaks loose, Gensini said.

Sometimes, the cold air mass splits into chunks — an event that usually is connected to big snowstorms in the U.S. East, like a few weeks ago. Other times, it just moves to a new place, which often means bitter cold in parts of Europe. This time it did both, Cohen said.

There was a split of the vortex in early January and another in mid-January. Then at the end of January came the displacement that caused cold air to spill into Europe and much of the United States, Cohen said.

Both Cohen and Francis said this should be considered not one but three polar vortex disruptions, though some scientists lump it all together.

While both the vortex and the wave that bumped it are natural, and polar vortex breakdowns happen naturally, there is likely an element of climate change at work, but it is not a sure thing that science agrees on, Cohen, Gensini and Francis said.

Warming in the Arctic, with shrinking sea ice, is goosing the atmospheric wave in two places, giving it more energy when it strikes the polar vortex, making it more likely to disrupt the vortex, Cohen said.

“There is evidence that climate change can weaken the polar vortex, which allows more chances for frigid Arctic air to ooze into the Lower 48,” said University of Georgia meteorology professor Marshall Shepherd.

...

As for people thinking this cold outbreak disproves global warming, scientists say that’s definitely not so.

Even with climate change, “we’ll still have winter,” said North Carolina state climatologist Kathie Dello. “What we’re seeing here is we’re pretty unprepared for almost every type of extreme weather. It’s pretty sad.”

Related Content