Climate Change Continues To Melt Glacier National Park's Icons

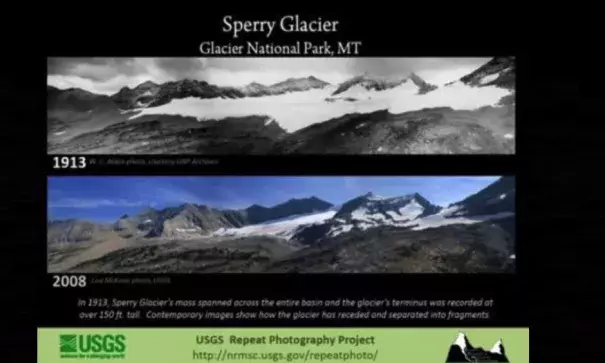

Sperry Glacier is still alive, its glacial melt spilling in long, wispy tendrils into Avalanche Lake in Glacier National Park. But whereas the size of Sperry in 1901 has been estimated by the U.S. Geological Survey at 3,237,485 square meters, today the mass has been shrunken to about 874,229 square meters; more than two-thirds of that behemoth that Albert Sperry described as "dying, dying, dying" having been lost to a warmer climate.

Against that history, and against recent years' predictions that Glacier would be glacier-less by 2030, last week's news that two of the park's glaciers, Shepard and Miche Wabun, had had their "glacier" status removed by the USGS because estimates of their masses had dwindled below 25 acres, was not earthshaking. It was eye-catching, though, as perhaps no other national park is so strongly connected with a single aspect of its contents as Glacier is with its glaciers.

...

Things appear even more daunting when you consider that "it has been estimated that there were approximately 150 glaciers present in 1850, and most glaciers were still present in 1910 when the park was established," the latest USGS analysis points out.

...

Glacier National Park is suffering from heat stroke, a malady that could melt all of its rivers of ice not by 2030, but by 2020. Such a prospect would send shudders not only across the park's landscape and through its plant and wildlife resources, but also deliver a jolt to Montana's economy. That message was rekindled last week by the Rocky Mountain Climate Organization, which released a 35-page report that, while not breaking new ground when you consider all the clamor that's been raised in recent years over a changing climate and its impact across the National Park System, does cohesively present both on-the-ground impacts and projected threats that will sweep across the 1-million-acre park and the resulting fallout, both biologically and economically.

Related Content