China Floods June - July 2016

From mid-June through July, China endured a series of extreme precipitation events and floods, including the remnants of a Category 5 super typhoon—Typhoon Nepartak. All together, officials report on July 26 that 833 people died and 270 were missing due to the series of disasters. The floods are the second-deadliest weather-related event of 2016 and the fifth most expensive weather-disaster on record outside of the US. The heavy rainfall fits the current pattern experienced in the warming world in which higher temperatures are driving more intense rainfall events.

China's historic floods are among the Earth's most costly weather-related disasters

In all, 833 people have died in weather-related disasters since June, with 270 missing. Total weather-related losses for the entire year have reached $44.63 billion (298 billion yuan), with about 400,000 houses destroyed and 6.24 million residents displaced.

- China's Ministry of Civil Affairs, reported on July 26 [1]

From June 14 through June 20, heavy rainfall and flooding in eight provinces in southeast China claimed 36 lives, displaced 200,000 people and caused an estimated $1.1 billion (7.34 billion yuan) in damages.[2]

From June 14 through June 20, heavy rainfall and flooding in eight provinces in southeast China claimed 36 lives, displaced 200,000 people and caused an estimated $1.1 billion (7.34 billion yuan) in damages.[2]

During the first week of July, torrential monsoon rains along a stalled frontal boundary near the Yangtze River killed 186 people, left 45 people missing, and caused at least $7.6 billion in damage.[3] With these losses, China's deadly floods became the world's most expensive and the second deadliest weather-related disaster so far in 2016.[3] In the Hubei Province, 1.5 million people were evacuated or in need of aid, almost 9,000 houses collapsed or were seriously damaged and more than 710,000 hectares of crops were affected, the provincial civil affairs department said.[3]

On July 9, Typhoon Nepartak made landfall in the already saturated Fujian Province, claiming 21 lives and leaving 13 missing.[4]

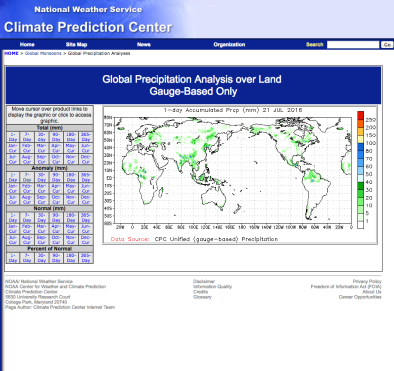

![]() On July 14, the Office of State Flood Control and Drought Relief Headquarters reported that, since early summer, the storms and floods had killed 237 people, left 93 people missing and caused at least $22 billion in damage.[4][5]

On July 14, the Office of State Flood Control and Drought Relief Headquarters reported that, since early summer, the storms and floods had killed 237 people, left 93 people missing and caused at least $22 billion in damage.[4][5]

At an economic cost of $22 billion, it is the fifth most expensive weather-related natural disaster on record outside of the US, according to the International Disaster database.[5]

From July 18 to 20, continuous downpours in China's Hebei Province and across usually dry regions, including the capital of Beijing, caused flash floods in mountains and serious waterlogging in some cities. Flooding and waterlogging—which is when water builds up and cannot drain for prolonged periods—of this magnitude have been tied to an increase in malaria and other infectious diseases.[6]

Official data show that this latest round of torrential rain and floods left 164 dead and 125 missing across 10 northern cities and provinces in China, with nearly 15 million others affected.[7]

Official data show that this latest round of torrential rain and floods left 164 dead and 125 missing across 10 northern cities and provinces in China, with nearly 15 million others affected.[7]

Water levels in Lake Taihu, close to Shanghai, reached their highest since 1954[8], and water levels in some major rivers exceeded those of 1998, when the worst floods in recent years killed 4,150 people, most of them along the Yangtze River.[9]

Extra water vapor means heavier rainfall

A warmer atmosphere can hold and dump more water. During the past 25 years, satellites have measured a four percent rise in atmospheric water vapor that is in line with the basic physics of a warming world and is consistent with the results of computer models simulating the current warming climate.[10][11]

Storms reach out and gather water vapor over regions that are 10-25 times as large as the precipitation area, thus multiplying the effect of increased atmospheric moisture. As water vapor condenses to form clouds and rain, the conversion releases heat and further fuels the storm.[12] This increases the gathering of moisture into storm clouds and further intensifies precipitation.[13]

Over the last three decades, the number of record-breaking rainfall events globally has significantly increased, and the fingerprint of global warming has been documented in this pattern.[14][15]

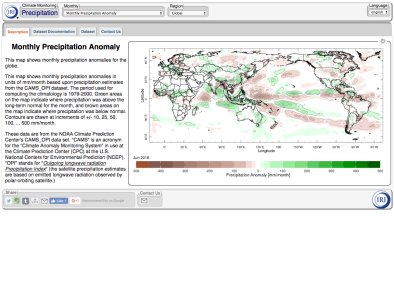

The Yangtze Valley of China is among the locations where a significant increase in summer precipitation was found to occur during the 20th century.[5][16]

East Asian monsoon shift linked to seasonal rain changes

A multiyear series of studies using high-resolution global circulation models (20 km), led by Shoji Kusunoki (Japan’s Meteorological Research Institute, or MRI) and colleagues, found that both average and extreme precipitation in the Mei-yu zone will increase during the 21st century.[17]

The research highlights that a shift in regional circulation—the east Asian monsoon—is likely to lead to a significant increase in total rainy season rainfall (from June to July) over almost all regions of East Asia.

Subsequent modeling has only strengthened this finding.[5]

The combination of El Niño and climate change can drive rains above prior record levels

The effects of El Niño are responsible in part for the intense rainfalls in China.

China’s vice-premier, Wang Yang, warned in June that a strong El Niño effect during the summer of 2016 would increase the risk of floods in the Yangtze and Huai river basins.[8] Experts have linked El Niño effects to China’s worst floods of recent years when more than 4,000 people died in 1998, mostly around the Yangtze, though the Beijing News quoted a meteorologist as saying rain patterns this year were more disparate than in 1998, diminishing the risk of a similar toll.[8]

As global warming loads the atmosphere with more moisture, the combination of El Niño and climate change can drive rains above prior record levels.

Related Content